Letters from Arrakis

Part 2: In which we talk about the Fremen and their Arrakis

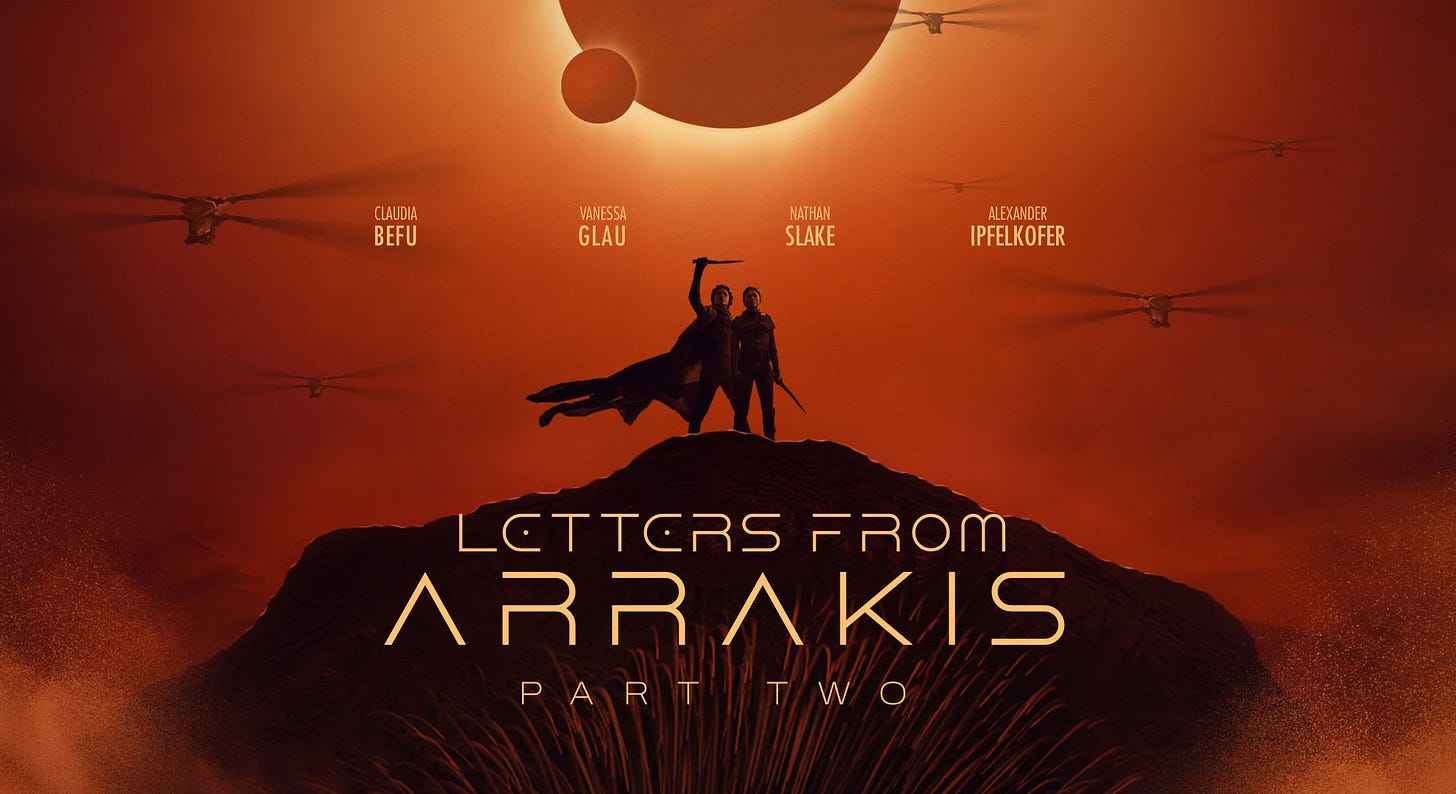

First time here? Story Voyager is a climate fiction newsletter I email to subscribers. Currently, I’m reading Dune with Nathan, Alexander and Vanessa, and we’re sharing our impressions in a series of four Letter from Arrakis. If you want to read with us, you can start here.

In the first letter from Arrakis, we discussed Book One, the worldbuilding of Dune and our impressions after rereading the book for the second or third time. In the second letter, we focus on Book Two, the Fremen and their long-term mission to green their beloved desert planet, Arrakis. We will also discuss how Paul and Jessica take advantage of the Fremen situation on Arrakis to reach their revenge goals and reestablish the Atreides House.

Unlock Your Reader Badge!

Alexander Ipfelkofer prepared these cool reader badges for you! Head to the comments section and confirm that you read Book One and Book Two to get your badges.

Book Two Synopsis

In Book Two, the narrative shifts to focus on Paul and Jessica. After being stranded in the harsh and dangerous desert sands, they encounter a group of Fremen. Following a test of leadership and power, they are accepted into the sanctuary of the Fremen sietch, where they learn of the Fremen’s ways and means of survival on Arrakis. Book Two culminates with the ceremony of drinking The Water of Life – the liquid exhalation of a sandworm changed by a Reverend Mother – the catalyst for Paul’s transformation into the prophesied figure known as Muad’Dib. With his newfound powers of leadership, Paul must grapple with the weight of his prophecy and the many lines of fate he witnesses – events that await in Book Three.

Letters from Arrakis: Part Two

What is Dune’s secret staying power?

Alexander: I always found it fascinating that Dune got as big as it has and Frank Herbert was surprised as well as he said in interviews. The images of Dune seem to tap right into our brainstem. Such a powerful connection trumps any shortcomings the book may exhibit, including its science that magically works and does not hold up to scrutiny, aka the Holtzman Effect, which requires us to suspend disbelief and so we do.

Claudia: This is an interesting take, Alexander.

Alexander: The worldbuilding in Dune is certainly clever, a pastiche, inspired by and drawing from existing concepts, people, and places. Dune is one big work of rhythm, it connects with the reader on this primordial level, appealing to the ancient parts of our brains with ideas centered around tribalism, mystical powers, and superstition.

Frank Herbert used his knowledge to examine themes of ecology, power, politics and so forth. He spoke on the ‘Origins of Dune’ in his 1969 interview with McNelly, an interesting conversation. Even more interesting is how Denis Villeneuve transported the emotional part of Dune onto the screen with incredibly sensory images, visualizing what the world of Dune feels like.

Nathan: Good observations. I do agree though that there are strong spiritual threads in the book, which really start to become evident once we witness Paul’s transformation, and likely helped sustain the cultural appreciation of Dune. Frank must have been interested in spiritual connections to the soul and the nature of consciousness, as well perhaps dabbling with a psychedelic substance or two.

He could still taste the morsel she had fed him – bird flesh and grain bound with spice honey and encased in a leaf. In tasting it he had realised he never before had eaten such a concentration of spice essence and there had been a moment of fear. He knew what this essence could do to him – the spice change that pushed his mind into prescient awareness.—Dune, Book Two

Nathan: Pretty much how I feel after a double shot of espresso.

Vanessa: If you replace spice with cinnamon, caramel, and chocolate, you could even say we get a similar religious experience out of Starbucks nowadays (without the hallucinations—I mean visions of the future, hopefully).

Nathan: If we’re going to touch again on worldbuilding then I’ll make a comment: Book Two is the most interesting because we learn a lot about the Fremen culture and how they survive on a seemingly inhospitable world, not only their adaptation but also their reverence for the planet, its life and, of course, its water. These were far more interesting themes for me than those of Book One.

Claudia: Readers are asking on forums why Arrakis didn’t import water. They probably haven’t seen the Guild’s invoices for transportation. (laughs) Frank Herbert, who later on in life dubbed himself a technopeasant, has a keen interest in ecology, and his Dune is an ecological science fiction, which makes Herbert a pioneer of climate fiction. The planet Arrakis is the main protagonist of Book Two, ever-present through the hardships that it imposes on the Fremen—the lack of water and consequently food, the oppressive heat, the unforgiving sand storms—but also its blessings—the sandworms and the spice. The lives of the Fremen are dictated by Arrakis, their technology, their survival skills, and their dream of greening their beloved desert planet. Regarding worldbuilding, it appears that Frank Herbert took some inspiration from a 1960 novel called The Sabres of Paradise by Lesley Blanch that depicts the story of Imam Shamil, the political, military and spiritual leader of the North Caucasus against Imperial Russia. Some examples: the kindjal knife, the Fremen sietch, the Chakobsa language, and the hawk features of the Atreides that resemble the eagle features of the North Caucasus people all come from Blanch’s book.

Nathan: I had no idea about that. Great info.

What do you make of the Fremen water economics? What images did you find most striking?

Vanessa: Herbert did an excellent job weaving the significance of water into Fremen culture in general. There are so many traditions and customs surrounding it, leading to beautiful quotes like this:

This is the bond of water. We know the rites. A man's flesh is his own; the water belongs to the tribe.—Dune, Book Two

Vanessa: There is also an element of mystery, as they have to keep their huge water stores secret from the official rulers of Arrakis, and the religious overtones lead right back to the prophecy and Paul.

Claudia: I found the Fremen water lore fascinating.

Nathan: Yeah, again I think these were the highlights of Book Two. The moment of the sietch water cache being revealed to Jessica and Paul is powerful because it deepens your respect for the Fremen and their true knowledge and harmony with Arrakis.

Beyond the barrier in the glow of Stilgar’s globe, Paul saw an unruffled dark surface of water. It stretched away into the shadows – deep and black – the far wall only faintly visible, perhaps a hundred metres away.

[…]

‘It is greater than treasure. We have thousands of such caches.’—Dune, Book Two

Alexander: When talking about Fremen water economics one cannot not talk about death stills and while this may not be explicitly pictured in Dune, it is a striking image placed in our minds, this ritual, the dead being burned to recover their body’s water.

“Fremen death stills made ashes of all flesh to recover a body’s water.” —Heretics of Dune, Chapter 30.

Claudia: Wouldn’t the water evaporate though?

Frank Herbert: It works because I want it to.

Nathan: Strange, I thought I just heard something. So it took until the fifth book to explain the process? Bodies are simply carted off for that process in Dune.

Claudia: I watched the 2013 documentary ‘Jodorowsky’s Dune,’ and I had the impression that the Chilean director focused on the religious aspects of Dune in his 70s project to film the book. He planned to make a very psychedelic movie. In 2021, Villeneuve had a ‘clean’ version of Dune, minimalistic compared to Jodorowsky’s vision. The ecological themes are subdued but ever-present. There’s the scene where Gurney says, ‘To shower you scrub your ass with sand,’ the scene where Stilgar spits on the Duke’s table, there’s the still suits, there’s Muad’Dib, the desert mouse that recycles its sweat. Nowadays, we underestimate the importance of water in human history, but the first empires were hydraulic and maintained power by controlling access to water. They even invented advanced mathematics to manage complex water distribution and irrigation systems. With the current climate crisis, water is becoming a main preoccupation again, and Dune is an excellent cautionary tale.

… and they were caught between wild Fremen whose only interest was the water carried in the flesh of two unshielded bodies.—Dune, Book Two

Vanessa: This would definitely be a clever way of giving the story renewed relevance, connecting it to current events. It’s amazing that the material is already in the book.

Nathan: Although the relevance of water is there in the film (or, rather, water is evident by its absence), the film places a stronger focus on the political dangers, as well as those of the wildlife…

Alexander: Part One was more focused on driving home Paul’s journey and the ‘Desert Power’ message, e.g. the whole Dinner scene was cut, where Duke Leto has the water basins removed and changes the local customs of ‘wasting’ water and servants selling the soaked towels for profit. We get less of this ecological thread in direct tells, but the visual contrast, the juxtaposition of abundance (Caladon)—Paul dips his hands into the ocean when the ships depart versus harsh scarcity on Arrakis when he is out to inspect the Spice Harvester and lets sand run through his fingers—is clear. This thread from abundance to scarcity of water is an integral part of the movie.

Vanessa: I hope Part Two shows more water vs. desert imagery to show its importance to the Fremen, showcase their culture. In many ways, the film did what Herbert should have done: show don’t tell!

What do you think of Paul and Jessica’s exploitation of the Fremen religion?

Vanessa: At first, the Missionaria Protectiva is portrayed merely to provide shelter to Bene Gesserit on Arrakis–without it, Dune would have ended with the assassination of Duke Leto. The longer Paul and Jessica stay with the Fremen, however, the clearer it is that they use their religion to their advantage. Paul struggles against his prophesied fate because he knows it will involve large-scale bloodshed but recognizes the necessity of manipulation all the same. I have mixed feelings about this. Dune paints him as the hero who gives the Fremen new purpose and courage even though he pushes them towards extremism. If Herbert were to publish today, this would likely be regarded as highly problematic and he would be asked to rewrite it.

Claudia: I am unsure whether Herbert thinks Paul’s role is necessarily good. Paul seems to struggle against his fate while taking all the necessary steps to make it happen. His ascent to power is complete by the end of the book. Whatever motivations he and his mother have, their interactions with the Fremen lead to fatal results. Nothing good can come out of this. And I feel this is ultimately Herbert’s message.

Vanessa: No, Paul is not portrayed as morally good. He is the hero only in the sense that he gets the most time on the page (and the screen). He might be more of an antihero.

Alexander: Spoiler Alert. Frank is setting Paul up for failure.

It will not be, he told himself. I cannot let it be. —Dune, Book Two

Nathan: From a narrative point of view, Paul’s transition from innocence to arrogance was too rapid for my tastes. But that’s a Book Three discussion.

Alexander: Paul’s arrival on Arrakis and the Spice accelerates his transformation. Embracing his role as the “chosen one” does seem foreign, at his age even, especially since he only wants to be a son (in Book One) but realizes that he is a monster. When asked by the Fremen what they should call him, he chooses the name Muad’Dib, an indication that he may be on board with the leader role (having seen a/the future) but not so much with leading the Fremen into a jihad. In that, he does not embrace his role.

‘How do you call among you the little mouse, the mouse that jumps?’ Paul asked, remembering the pop-hop of motion at Tuono Basin. He illustrated with one hand.

A chuckle sounded through the troop.

‘We call that one muad’dib,’ Stilgar said.

[…]

And again he remembered the vision of fanatic legions following the green and black banner of the Atreides, pillaging and burning across the universe in the name of their prophet Muad’Dib. That must not happen, he told himself. — Dune, Book Two

Nathan: There’s Jessica’s influence to consider, too. In response to Stilgar’s words about the caching of enough water to alter the planet, she thinks:

Jessica felt the religious ritual in the words, noted her own instinctively awed response. They’re in league with the future, she thought. They have their mountain to climb. This is the scientist’s dream … and these simple people, these peasants, are filled with it.—Dune, Book Two

What is the Fremen’s goal and has outside exploitation forced their hand?

Claudia: The spice must flow… like oil. If you do a quick Google search, you will find many articles linking the spice melange to oil. But the exploitation of local resources by powerful empires started long ago. Take the Roman Empire and their thirst for timber. There is even a concept called the ‘resource curse’. Countries rich in natural resources (paradox of plenty) are less developed than countries with fewer natural resources (poverty paradox).

Vanessa: I wonder what Herbert intended when he used terms like race and race consciousness. Political correctness aside, both this and the need for jihad seem to be portrayed as the ultimate means of survival for the Fremen:

They were all caught up in the need of their race to renew its scattered inheritance, to cross and mingle and infuse their bloodlines in a great new pooling of genes. And the race knew only one sure way for this—the ancient way … jihad.—Dune, Book Two

Vanessa: I agree that they were shaped by their environment and outside exploitation might have left no other way but I’m not sure if it excuses extremism.

Nathan: I took “race consciousness” to mean something more akin to “collective consciousness”, which would perhaps be a better term in today’s, ah, climate. Along with Paul’s “terrible purpose”, it’s a phrase that feels oversaturated through the book.

He sensed it, the race consciousness that he could not escape. There was the sharpened clarity, the inflow of data, the cold precision of his awareness.—Dune, Book Two

Nathan: The Fremen crave a terraformed planet for future generations, but my interpretation was that their adaptation to Arrakis was something they accepted and were at one with. Their sietches are places of community and (at times) happiness, despite the living conditions. They have lusher land to the south— though we only get secondhand glimpses of that in Book Two—and have been caching vast amounts of water in secret.

Alexander: The Fremen take pride in their way of life. They want a better future, and Kynes’ father planted the seed for that with the idea of transforming (parts of) Arrakis into a garden. The desert is harsh, the Fremen are depicted as living in it in harmony and not too keen on changing their ways. Paul is that catalyst for change. Towards what future, though?

Nathan: It’s actually unclear to me what role the Fremen felt Mahdi/Lisan Al-Gaib would play in the future of Arrakis in terms of turning it into a paradise. In Book Two Stilgar speaks of their plans and the necessity to cache enough water, saying ‘We know to within a million decalitres how much we need. When we have it, we shall change the face of Arrakis.’ To which all the Fremen amen their assent.

‘We change it … slowly but with certainty … to make it fit for human life. Our generation will not see it, nor our children nor our children’s children nor the grandchildren of their children … but it will come. … Open water and tall green plants and people walking freely without stillsuits.’

So that’s the dream of this Liet-Kynes, she thought.—Dune, Book Two

Alexander: It may stem from the fact that in the first draft, Herbert had Kynes as the main character. Kynes did all the work to get started on terraforming Arrakis, no need for a greenhorn to come and mess things up, and yet, this is what happens, because the Bene Gesserit want to control everything, meddling witches.

Finally, what is your biggest takeaway from Book Two?

Claudia: Water rings!! I got very thirsty while reading book two. Then I thought about buying a house next to a river. Or a water spring. I’m very thirsty right now (drinks a glass of water, gulp, gulp). Also, isn’t the swearing great?

Do as she says, you wormfaced, crawling, sand-brained piece of lizard turd!—Dune, Book Two

Nathan: My take: that it’s better than Book One? That an editor actually allowed the line “Um-m-m-mah-hm-m-m” to be printed? That the word “elfin” is now permanently associated with Zendaya Chani in my mind?

Claudia: I don’t think Frank Herbert had Zendaya in mind when he wrote Chani…

Nathan: OK, I suppose you want a serious answer. Of the three books (yes, yes, I’ve read ahead already), Book Two is my favourite. A loose term, because I don’t love Dune, at all, but if I had to rank the sub-sections then I’d put Book Two first. It made me care about The Fremen. I cared about Kynes until their demise. I’m fascinated by the caches of water, the techniques used to survive and thrive in a world that seems inhospitable, the intrigue of the polar regions, the little makers and the spice and its psychoactive properties, the long long long-term plans for changing the planet. All these lovely elements are there. They’re the rich texture of a world well-realised, but one obfuscated by weak prose, in-your-face exposition and the … (yawns) … oh, sorry, fell asleep there whilst I was skimmed back through the pages. (We also haven’t spoken anything at all of Feyd Rautha and the Baron, but we can save that for next time.)

Vanessa: I agree that Book Two is the strongest. We learn more about the Fremen, their social hierarchy, how they live and what moves them. Fictional cultures are always a favorite of mine. I also enjoyed seeing new facets of familiar characters–with the exception of Paul who has been getting more annoying. If I remember correctly, Book Two is where I lost interest in Dune on my first read. I'm definitely losing patience this time around too, although for different reasons: namely the writing style and the reluctant messiah trope we see in Paul. Let's see how Book Three treats us.

Alexander: I am with Nathan on the prose and must confess I hoped to enjoy Book Two more than I did, but ultimately I found it to be a slog. So, Jessica becomes the new Reverend Mother, prompting “a rite of joining,” a Spice Orgy. Let Shai-Hulud judge now!

How will Dune – Part Two handle that? Going to be cut? Taking bets now. Frank Herbert wrote Dune in the 60s when drug experimentation was entering the mainstream consciousness of America, so the inclusion of mind-altering drugs comes as no surprise. Book Two was supposed to be (and is) about Muad’Dib, yet, it’s Jessica who “ascends” and sets the stage for Alia.

Now to You

Did you finish reading Book Two? Head to the comments to get your reader badge! And to let us know your impressions.

Does Dune’s ecological theme resonate with you?

What is your biggest take away from Book Two?

Our next letter from Arrakis, covering Book Three of Dune, will be delivered by ‘thopter on February 15, 2024. Until then, The Spice Must Flow.

Letters from Arrakis – Reader Badges

Grab them here: First Letter Badge | Second Letter Badge

Thanks for this lovely long post, I really enjoyed the conversation about the book. I have yet finished the book two and tried to not read the post till I finished but here I am because in all likelihood, I won't be able to finish book three before Feb 15.

I feel this is Arabian Nights in space. the draw for me was the worldbuilding and unlike most books I've read, aside Tolkien, Dune delves deeper into sands of Arrakis in its ecology and how it shapes the culture, ultimately shaping one's ways of thinking.

It sounds weird and otherworldly but it wasn't too long ago families cared about maintaining the bloodline and this book explores that aspect in a bigger picture as maintaining race. I think it's interesting to read today due to sharp declining of birth rates in some countries creating some panic over the ethnic group would wither away; Japan and Korea such example. Such notion is not really a thing for North Americans since this is a new continent with short history of melting pot of people and culture from the old world. Thus our understanding of nation and ethnicity are not directly tied but in the old world that is the case and Herbert must have taken that as fantastic coming from the new world (American).

So far I like the exploration of the cultures around water and the language Herbert uses to show how Fremen think and do is shaped by their ecosystem; lizard dung must have near zero water because it's used as an insult. I somehow wish we can explore the world more.

um, on a side chuckle on Nathan's second point of saying Ums and sounds, I used to write that in my short stories when I was young because that's what I read in Dune. It's irritating and oddly refreshing for me because there are so many books about how people in the book don't talk like we do but in Dune they somewhat do, and that difference somewhat makes it unique.

I was refreshing to read your comments and insights about the book and looking forward to the third one!

Fantastic work folks! These collaborations are filled with great insights and I enjoy that you allow your personalities to come through (at least what I envision your personalities to be). The format reminds of the mid-point break in a graduate lit class, when the discourse continues but without the pedantic structure of a lecture and discussion. Keep it up!