When I was five and a half years old, my mother taught me how to read and write. Although she was a teacher, she couldn’t work in a school because she wasn’t a member of the communist party. Instead, she worked in a factory weaving Adidas textiles. In communist Romania, wearing capitalist brands was forbidden, but being cheap labor producing capitalist products for export was a service to the society. So, my mother gave me homework before she left for her factory shift. I could read by the time I was six, and she gifted me my first book.

While fairytales were a childhood favorite, it was the communist children’s books that left a lasting impact. Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceausescu adored children, and those born within the party were considered the future. The books I grew up with depicted children as little geniuses who contributed to society’s betterment—for example, by making major scientific breakthroughs at nine. Ultimately, science [fiction] couldn’t solve the systemic issues of a totalitarian government, and in 1989, communism fell, and the dictator and his wife were shot by the same children whom they claimed to love.

Recently, I’ve noticed a new crop of climate fiction literature focused on saving the planet within the next 200 years. With the help of writing prompts, climate fiction writers are encouraged to imagine how they personally helped save the world by a specific date through their actions. The resulting stories remind me of the communist children’s books I read at the end of the 1980s. While I appreciate the hope they inspire, I can’t help but notice a massive disconnect between our aspirations and the practical challenges we face.

Take the European Union’s push for carbon neutrality by 2050, for example. While commendable, it’s undermined by slow progress in digitalizing grids necessary for renewable energy integration. Estonia is the only EU country that used blockchain technology to succesfully digitalize its grid. Meanwhile, in an effort to transition away from fossil fuels, the UK plans to obtain renewable energy from Africa via underwater cables along the Atlantic Ocean coast.

As someone who has worked in the energy industry for the past two years and has a background in project and product management, I understand the enormity of the task at hand: switching from fossil fuels, the main culprit for global warming, to renewable energy in a world increasingly hungry for energy. It didn’t take me long to understand that despite our best efforts and intentions, we're not making any progress.

The CO2 emissions aren’t declining

In the battle against global warming, one primary culprit is burning fossil fuels and one key measure of success is reducing CO2 emissions.

Here’s a chart from Statista showing the average global CO2 levels in the atmosphere worldwide from 1990 to 2024. It doesn’t take a genius, communist child or otherwise, to see that they're not declining.

Meanwhile, countries worldwide have taken serious action against climate change for the past two decades, and the CO2 balance is moving in the right direction on paper. However, while the carbon certificates economy is thriving, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is booming.

According to the European Environment Agency, there was a 31% reduction in CO2 emissions in 2022 in Europe compared with 1990s values. The EU accounts for 6% of global emissions as the fourth largest emitter. But according to this article, the CO2 emissions from energy, the biggest source of emissions by far, increased by 1% globally in 2022.

On the other hand, according to NRCD, China, India and the United States, the top three largest emitters of CO2 worldwide, ‘are coordinating and cooperating at levels never seen before in order to tackle the most pressing issue of our time’. Are they making any difference? Not according to this and this statistic. Let’s check the numbers.

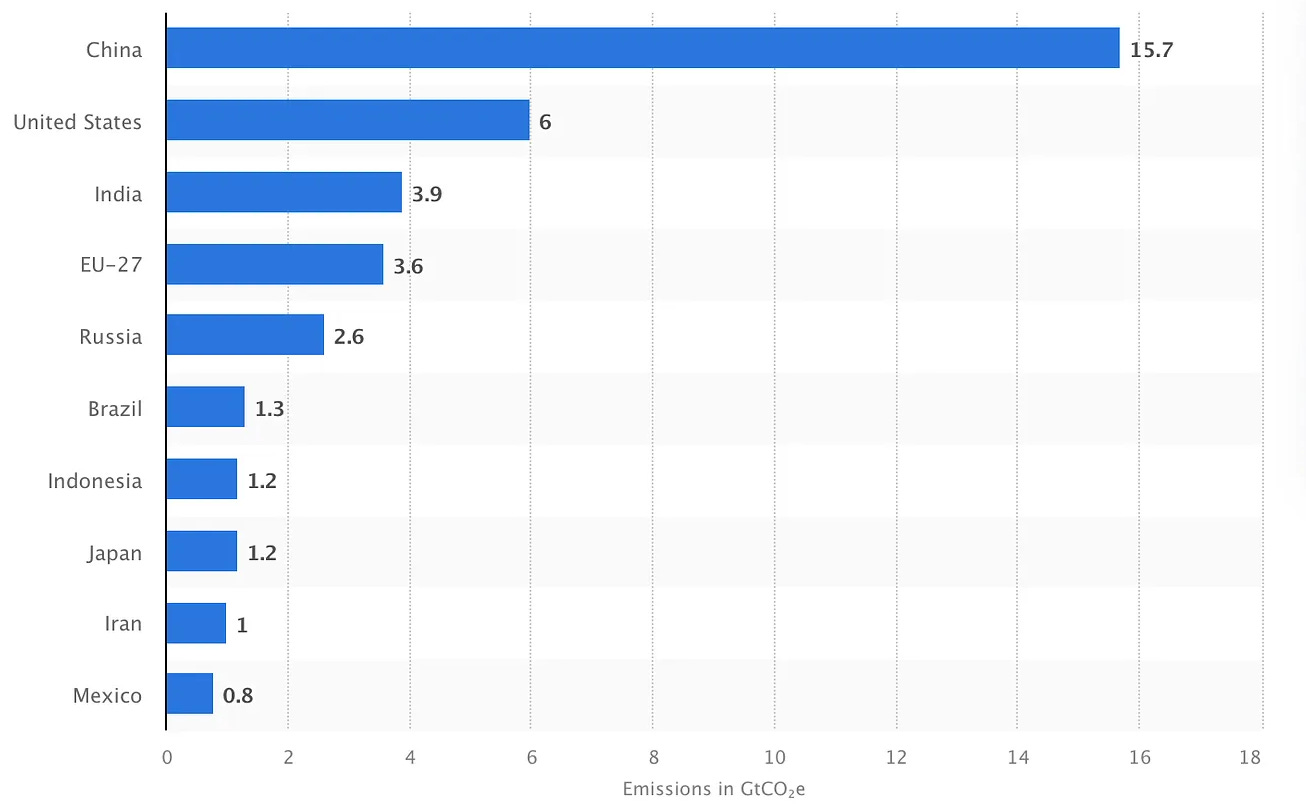

These are the CO2 emissions of the top four polluters worldwide in 1990 in billion metric tones:

United States → 5.12

EU-27 → 5

China → 2.5

India → 0.6

These are the CO2 emissions of the top four polluters worldwide in 2022 in billion metric tones:

China → 15.7

United States → 6

India → 3.9

EU-27 → 3.6

Here’s the only top 10 chart in the world on which nobody wants to be listed.

Here are the cumulative CO₂ emissions of the top 5 most polluting countries in the world from 1750 to 2022 in billion metric tones:

United States → 426.9

China → 260.6

Russia → 119.3

Germany → 94

United Kingdom → 78.8

For a one-ppm increase in CO2 atmospheric concentration, a total of 7.8 billion metric tons of CO2 need to be emitted. The United States alone contributed with an increase of 54 ppm from 1750 to 2022. To give you a simple overview, in 1750 there was a CO2 concentration in the atmosphere of approximately 277 ppm. In 2020 we had 417 ppm on average, in February 2023 a concentration of 420.3 ppm, and in February 2024 of 424.55 ppm.

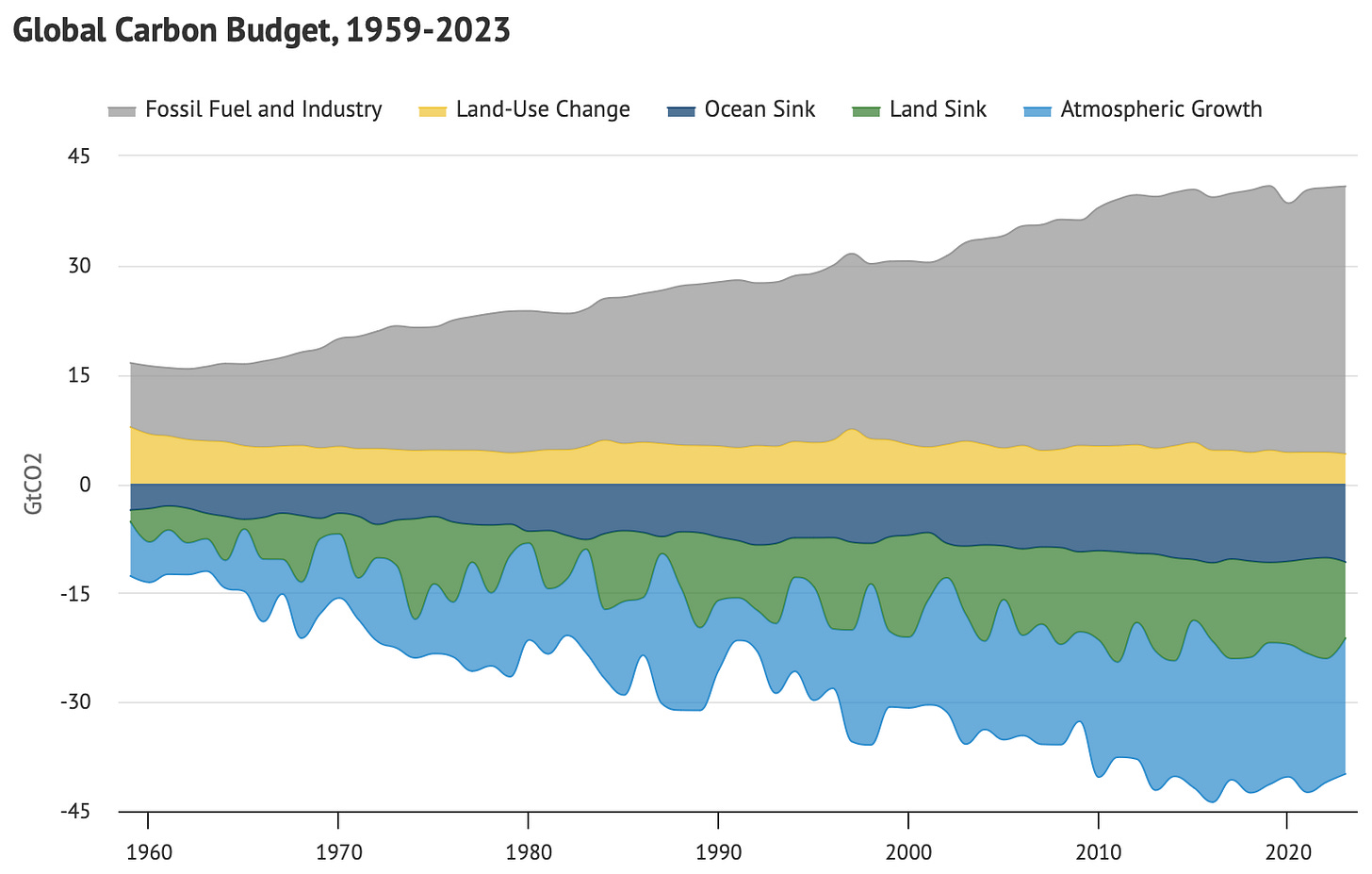

Fortunately, a partnership managed to effectively 'coordinate and cooperate' in the fight against climate change: the oceans, the soil, and the atmosphere of the planet, which we're so bent on setting up in flames. But, as I wrote in my article Climate change started thousands of years ago, their capacity to process and store CO2 is reaching a saturation point.

Once that point is reached, the current CO2 emissions levels will lead to faster global warming. Once we pass the 2°C threshold of global warming, scientists can no longer model and predict how our planetary systems will react. We are in unknown territory, and the consequences of climate change’s will be much harder to control.

Our global energy needs are the main driver behind the surge in CO2 emissions in the past 60 years and why we’ve been unsuccessful in our fight against climate change. We can clearly see a sharp dip in emissions in 2020, the year human activity around the globe came to a halt due to the pandemic. In 2023, fossil fuels covered over 80% of our global energy needs. Cities account for over 70% of global CO2 emissions.

When it comes to energy, electricity is the sector in which we’ve seen the highest surge in renewable energy production in the past years. But even so, over 60% of our global electricity production in 2023 was generated by fossil fuels.

‘Total energy-related CO2 emissions increased by 1.1% in 2023’ based on the annual CO2 emissions report of IEA, the International Energy Agency.

Far from falling rapidly - as is required to meet the global climate goals set out in the Paris Agreement - CO2 emissions reached a new record high of 37.4 Gt in 2023.—IEA

Our thirst for energy has yet to show signs of being stilled anytime soon. According to Jeff Bezos, we should actually increase our energy consumption.

The most fundamental measure is energy usage per capita. You do want to continue to use more and more energy, it is going to make your life better in so many ways, but that's not compatible, ultimately, with living on a finite planet, and so we have to go out in the solar system.—Jeff Bezos

Meanwhile, Amazon drastically undercounts its CO2 footprint on this finite planet and pledges to run a net zero e-commerce empire by 2040 while increasing its CO2 emissions year after year. With such a mentality we won’t save the planet in the next 200 years.

Is there hope?

In my childhood books, under communism, there was great hope that today’s children would become tomorrow’s scientists, leading the world to a brighter future. Progress was seen through the lens of scientific advancement, and questioning the party’s ideology or worldview was forbidden. Similarly, the discourse about combating climate change focuses primarily on technological advancement, infrastructure, and inventions that sustain our current way of life. While dissenting opinions may not land us in jail, challenging our existing worldview, notions of progress, and materialistic perspectives is met with overwhelming resistance. There’s an illogical hope that we can solve our problems with the same mindset that created them in the first place.

However, this moment invites us to reconsider our values and life aspirations. Is consuming more energy truly a worthy life goal? Are material possessions the ultimate measure of success? Must progress be defined solely by consumerism? Ultimately, it won’t be technology alone that saves our species from disaster, but a shift in mindset. The form this shift takes remains uncertain, but one thing is clear: the future of our planet will bear little resemblance to our current existence.

Story Voyager is where we explore climate change through the lens of climate fiction or cli-fi. Under the motto ‘travel your imagination’, we embark on a journey of reading, researching, writing, and exchanging ideas with like-minded people. Let’s change the narrative about the future of humankind together. If you’d like to support this space even more, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your financial support will go toward commissioning illustrations for my first cli-fi series, There Is Hope.

You’ve amassed some damning evidence of our complete and utter failure to change things. Our need to consume and advance is pathological, especially here in my country. As you articulate here, the only answer is to want less. What’s not clear to me is how we get off that conveyor belt. Thanks for providing a continuous wake up call.

This is such an important essay, and I feel so at a loss for how to fix it. It feels so clear that we need to transition to green energy (which does appear to be happening rapidly) but we also need to drastically reduce livestock production (which doesn’t appear to be happening at all). There are also whole industries that are excessive and need to be eliminated (fast-fashion, etc.) I’d be very curious to learn your ideas for a post-capitalist society that would achieve this because I definitely think we need a huge overhaul of the capitalist system but I need to think through what that might look like in practice.