The fiction of climate change

Field notes for "There Is Hope"

A couple of months ago, I started to dive into climate fiction as a literary genre. I read my first cli-fi novel, Oryx and Crake, by Margaret Atwood, in 2006, a couple of years before climate activist Dan Bloom coined the term climate fiction. But I got a formal introduction to cli-fi as a literary genre by reading The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable by Indian author Amitav Ghosh who dedicated an entire book to exploring the meaning and importance of writing climate fiction.

Last Monday, I finished reading War girls by Nigerian author Tochi Onyebuchi, a fiction novel about two sisters caught in the middle of a Nigerian Civil War in 2172 in a world largely rendered unliveable by climate change and nuclear disaster. The historical Nigerian Civil War, known also as the Nigerian-Biafran War or the Biafran War, was fought between 1967 and 1970 and served as a basis for the book. Currently, I am reading the second volume in this series Rebel Sisters.

From this initial reading, climate fiction emerges as a literary genre that has two daunting tasks:

Making sense of the complex scientific, socio-political, cultural and regional aspects of climate change—the most urgent topic of our lives.

Re-introducing fantasy as an acceptable element in the echelons of serious literature currently preoccupied almost exclusively with navel-gazing.

The challenges of writing climate fiction

According to the Climate in Arts & History website, climate fiction as a literary genre ‘is rooted in science fiction, but also draws on realism and the supernatural’.

The two cli-fi books I have read so far are categorized as speculative fiction and adventure romance in the case of Oryx and Crake and science fiction in the case of War Girls. Margaret Atwood does not call her novel science fiction because it doesn’t deal with things ’we can’t yet do or begin to do.’ Nevertheless, as a genre, cli-fi must go beyond the realism associated with a contemporary serious novel because, as Amitav Ghosh points out, it needs to re-include nature as an agent of change and as a protagonist:

I do believe it to be true that the land here is demonstrably alive; that it does not exist solely, or even incidentally, as a stage for the enactment of human history; that it is itself a protagonist.

Yet climate fiction is anchored in the current climate crisis. Therefore its primary role is to address and warn of the consequence of anthropogenic global warming and the unpredictable events it could unleash on us.

They are the mysterious work of our own hands returning to haunt us in unthinkable shapes and forms.

But how can it accomplish this, in a world of politicians, corporations and a public who don’t agree that the current climate change is man-made? More, who believe that even climate scientists don’t have a consensus regarding climate change? In order to start as a climate fiction writer, I think that a set of fundamental questions need to be addressed.

Is global warming real?

According to the National Resources Defense Council, global warming occurs when CO2 and other air pollutants collected in the atmosphere absorb sunlight and solar radiation—that would typically bounce off the earth and escape into space—thus trapping heat and making the planet hotter. The concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is measured as parts per million or ppm. In 1800 the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere was 280 ppm. I checked the daily CO2 on CO2.earth, and it’s 420.58 ppm. So what did all this CO2 do to our planet?

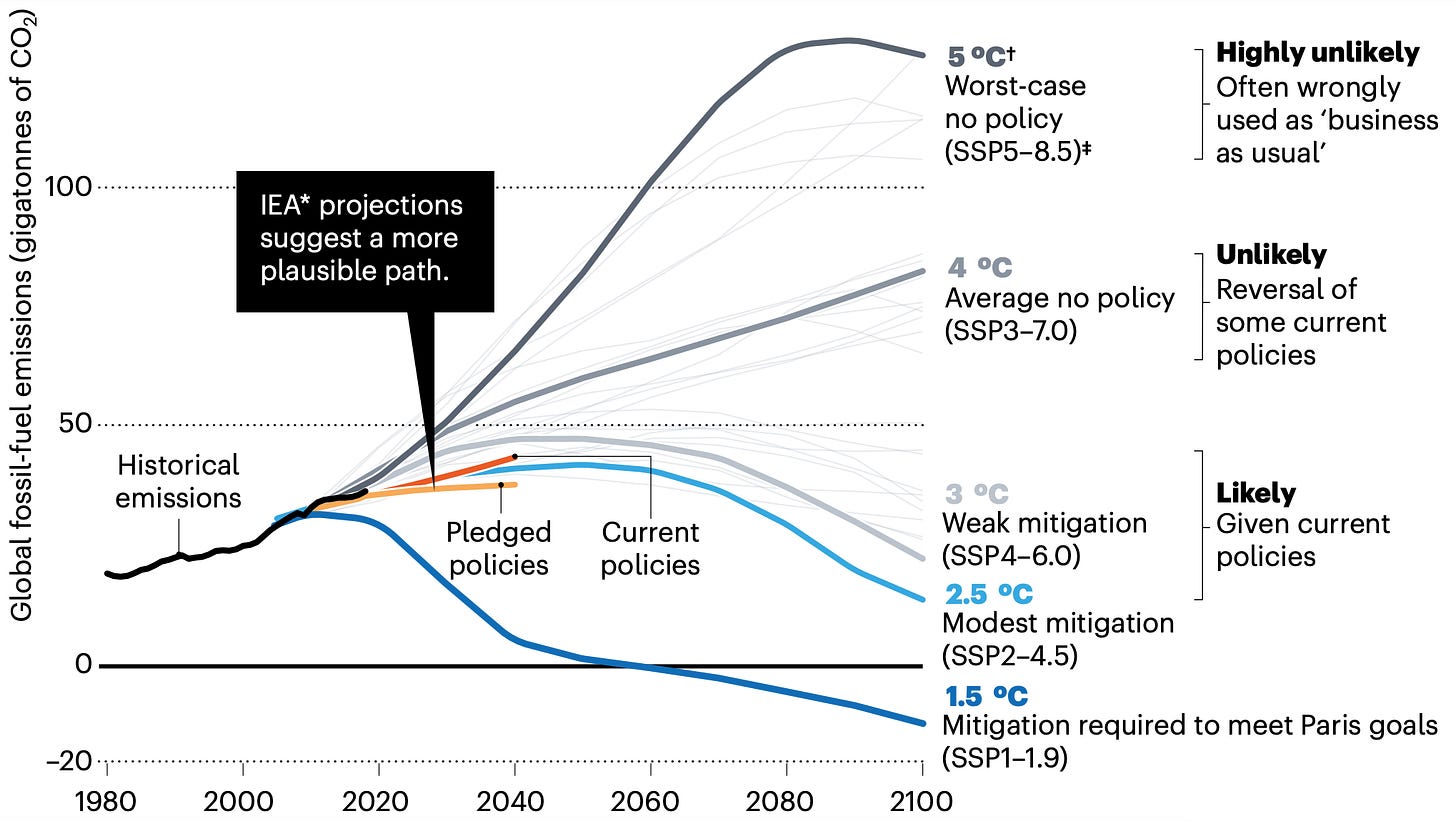

The global warming record-keeping started in 1880, and since then, the global annual temperature has increased by a little over one-degree celsius. Let’s keep in mind that only 50% of the CO2 emission from industrialization has gone into the atmosphere. The other 50% was absorbed by the ocean. So how much hotter can the atmosphere get? In a recent newsletter from Erik Hoel I found this helpful chart that shows the different global warming scenarios until the end of the century.

After that, depending on how we fare with global warming at the end of the century, multiple scenarios could play out. For example, if we get to five degrees celsius, we don’t know what other natural consequences could be unleashed. At some point the oceans will stop absorbing CO2 emissions, meaning that all the CO2 will be released in the atmosphere thus heating it up at even a faster rate. Thus rendering some regions on Earth uninhabitable. Thus raising the temperatures to a level where our favourite staple foods would be unable to grow.

So global warming seems pretty real but…

Is climate change man-made?

After analyzing the abstracts of 928 scientific papers on the topic of climate change submitted to scientific journals between 1993 and 2003, Naomi Oreskes, an American historian of science with degrees in geology and a specialization in the scientific methods, model validation, consensus and dissent, found that ‘without substantial disagreement, scientists find human activities are heating the Earth’s surface.’ This is how she elaborates:

For centuries, scientists thought that earth processes were so large and powerful that nothing we could do could change them. This was a basic tenet of geological science: the human chronologies were insignificant compared with the vastness of geological time; that human activities were insignificant compared with the force of geological processes. And once they were. But no more. There are so many of us cutting down so many trees and burning so many billions of tons of fossil fuel that we have indeed become geological agents. We have changed the chemistry of our atmosphere, causing sea level to rise, ice to melt, and climate to change. There is no reason to think otherwise.

As a good scientist, Naomi Oreskes is aware that the scientific consensus might be wrong. But are we willing to bet on it? I cannot put it better than the historian Dipesh Chakrabarty in his paper The Climate of History: Four Theses.

Not being a scientist myself, I also make a fundamental assumption about the science of climate change. I assume the science to be right in its broad outlines. I thus assume that the views expressed particularly in the 2007 Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change of the United Nations, in the Stern Review, and in the many books that have been published recently by scientists and scholars seeking to explain the science of global warming leave me with enough rational ground for accepting, unless the scientific consensus shifts in a major way, that there is a large measure of truth to anthropogenic theories of climate change.

Let’s say that we agree with the scientists that climate change is man-made, so…

Are we all going to die?

In 2021 the World Meteorological Organization published an article with the title Weather-related disasters increase over past 50 years, causing more damage but fewer deaths reporting that over the past fifty years there were five times more natural disasters caused by climate change but three times fewer human deaths due to early warnings and risk management.

Climate change leads to more extreme weather, but early warnings save lives.

This is a list of the top natural disasters that led to human loss between 1970-2019:

Generally, the consequences of climate change are felt locally, but they have a national and international effect due to how our world is interconnected. Below is a regional breakdown of the climate change damages recorded between 1970-2019:

Africa

A total of 731,747 deaths, of which 95% caused by droughts

Four droughts caused the majority of deaths: Ethiopia in 1973 and 1983 (total 400 000), Mozambique in 1981 (100 000) and Sudan in 1983 (150 000)

Economic damages: US$ 38.5 billion

Asia

A total of 975,622 deaths, of which 72% caused by storms

Economic damages: US$ 1.2 trillion

South America

A total of 34,854 deaths, of which 77% caused by floods

Economic damages: US$ 39.2 billion

North America, Central America, Caribbean

A total of 74,839 deaths, of which 71% caused by storms

Economic damages: US$ 1.7 trillion

South West Pacific

A total of 65,391 deaths, of which 71% caused by storms

Economic damages: US$ 163.7 billion

Causes for economic damages: storms (46%), floods (24%), drought (17%) and wildfire (13%)

Europe

A total of 159,438 deaths, of which 93% caused by extreme heat

Two extreme heat events from 2003 and 2010 caused 80% of the deaths

Economic damages: US$ 476.5 billion

It doesn’t look like we’re all going to die, but the economic impact of climate change seems quite depressing, so…

Are we all gonna be poor?

The first serious talks on global warming began in the late 1980s and beginning of the 1990s, and one of the most prominent political reactions to climate change science of those times came from George H. W. Bush in his 1988 electoral campaign:

Those who think we are powerless to do anything about the greenhouse effect forget about the White House effect. As president, I intend to do something about it.

Since George H. W. Bush didn’t manage to fight the greenhouse effect with the White House effect back in 1988, here we are today testing capitalism’s ecological limits, and it looks like a losing game. Below is an overview of the top 10 economic losses due to climate change during 1970-2019:

More interesting numbers from the economic losses suffered because of climate change in this 50-year period:

Daily average losses between 1970-2019: US$ 202 million

Daily average losses between 1970–1979: US$ 49 million

Daily average losses between 2010-2019: US$ 383 million

Economic losses increased sevenfold from the 1970s to the 2010s

Most prevalent cause of damage: storms

Most costly storms: Hurricanes Harvey (US$ 96.9 billion), Maria (US$ 69.4 billion) and Irma (US$ 58.2 billion)

So this doesn’t look very promising, but…

What if I don’t believe in climate change?

The other day my husband said that there are three things that he learned from working with data:

Data is either universally true, partially true or is what we want it to be true.

When it comes to climate change, the science is there, the data is there, the natural disasters and the climate activists are there, and yet the answers to two very essential questions are missing:

What does the climate change data mean to us as human beings?

And more importantly, what do we want it to mean to us?

The answer to the latest will pave our way into the future.

In 1633 Galileo Galilei was trialed by Rome and placed under house arrest after being threatened with a burning at the stake for believing that the sun and not the earth is the motionless center of our universe. It took the Catholic Church 359 years to apologize for the Galileo Case.

The scientific revolution during the Renaissance challenged the belief system of those times and set the basis for the Enlightenment, which brought a massive change in thought and reason and upended centuries of custom and tradition in favor of the rational humanity. This is how the modern world was born, with humanism at its center. Fast-forward 350 years, and you find the rational humanity at the mercy of nature’s irrational forces set in motion by ‘the mysterious work of our own hands returning to haunt us in unthinkable shapes and forms’.

The way forward requires not only science and data but also a revolution of the mind and a willingness to understand and accept that we humans have acquired powers capable of changing the fabric of our planet in fundamental ways. How can the rational humanity reason its way out of this existential dilemma? Amitav Ghosh thinks that we can imagine the future of humanity with climate change through climate fiction.

…to imagine other forms of human existence is exactly the challenge that is posed by the climate crisis: for if there is any one thing that global warming has made perfectly clear it is that to think about the world only as it is amounts to a formula for collective suicide. We need, rather, to envision what it might be. But as with much else that is uncanny about the Anthropocene, this challenge has appeared before us at the very moment when the form of imagining that is best suited to answering it—fiction—has turned into a radically different direction.

Climate fiction is the most important literature of our time. By imagining the future of humanity through climate fiction, we can answer the question of what we want climate change science to mean for the human species.

I intend to explore my imagination by reading some of the best cli-fi novels out there and by writing a collection of cli-fi stories.

My cli-fi reading list for 2023

I’ve selected 12 books and a poem as my curriculum for studying climate fiction in 2023. The beauty of using fiction as a medium for imagining the future with climate change is that every writer will have a unique take on what this future could be. So I am really excited to dive into these books.

1. War Girls by Onyebuchi Tochi

In January and February, I am reading volumes one and two of the africanfuturist climate fiction series War Girls by Tochi Onyebuchi (who by the way writes the Substack letterItalics), War Girls and Rebel Sisters, which takes place in Nigeria and outer space. It’s a well-written series, especially the second book, and it reminds me a bit of the sci-fi written in the 1980s.

2. Darkness by Lord Byron

In March, I am reading Darkness, an apocalyptic story by Lord Byron considered one of the oldest climate fiction writings. It was written in 1816, also known as the year without a summer, because of the eruption of the volcano in Mount Tamora that cast enough sulfur in the atmosphere to reduce global temperature and cause abnormal weather.

3. MaddAddam by Margaret Atwood

In March, April and May, I will re-read one of my all-time favorite novels, Oryx and Crake (2003) and read for the first time the second and third books in the dystopian trilogy MaddAddam: The year of the Flood (2009) and MaddAddam (2013). This is what James Kidd of The Independent had to say about the trilogy:

Atwood's body of work will last precisely because she has told us about ourselves. It is not always a pretty picture, but it is true for all that.

4. The Wind Up Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi

In June, I will read The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi, which was recommended by Oleg from Fictitious and is a biopunk science fiction that takes place in Thailand. The Wind Up Girl won the Nebula and Hugo awards for the best novel in 2010. This is what Sacramento Book Review had to say about this book:

Reminiscent of Philip K. Dick’s Blade Runner.... densely packed with ideas about genetic manipulation, distribution of resources, the social order, and environmental degradation ... science fiction with an environmental message, but one that does not get in the way of its compelling story.

5. Earthseed by Octavia E. Butler

In July and August, I will read Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents from the Earthseed series by Octavia E. Butler.

The Earthseed series is set in a future in which California faces severe income disparity and water shortage while the U.S. populace rallies around an extremist presidential candidate who wants to return America to white Christian Americans with patriarchal family values.

Earthseed is a religion with three central tenets: God is Change. Shape God. The destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars. Like Dune by Frank Herbert, it follows the story of a protagonist who will become a god after her death. I’m very excited about this series!

6. The Broken Earth by N. K. Jemisin

In September, October and December, I will read The Broken Earth trilogy by N. K. Jemisin: The Fifth Season, The Obelisk Gate and The Stone Sky. I discovered this author many years ago in an interview with Ann Leckie after I read her Imperial Radch trilogy, which I absolutely love. All the books in The Broken Earth trilogy won the Hugo award for best novel for three consecutive years. This is what The New York Times had to say:

Jemisin’s hubristic high-tech civilization, which brought about its own doom and birthed the brutal and seemingly inescapable pattern of life in the Stillness, is not quite ours. Indeed it feels like only one conceivable future, and not the worst imaginable: It’s a better organized, more utopian and also more totalitarian society than any we have yet created.

7. The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

In November, I will read The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley which comes highly recommended by several people including Daniel Martin Eckhart and is included in the utopian reading list of Elle Griffin of The Elysian (I'll definitely join her on the Threadable App in November for this one). This is what The Guardian has to say about the book:

Robinson shows that an ambitious systems novel about global heating must in fact be an ambitious systems novel about modern civilisation too, because everything is so interdependent. Luckily, when he opens one of his discursive interludes with the claim “Taxes are interesting”, he makes good on it within two pages. There is no shortage of sardonic humour here, a cosmopolitan range of sympathies, and a steely, visionary optimism.

This is my cli-fi reading list. The next step—besides reading— is to think of a structure for analyzing the futures imagined in these novels and understanding how they address climate change issues through dystopian (the outcome of dealing improperly with climate change) or utopian (the outcome of dealing correctly with climate change) scenarios.

Do you also read climate fiction? Are you interested in reading climate fiction? Do you think climate fiction as a literary genre is needed? What do you expect to see in climate fiction literature? Let me know in the comments.

I once listened to a futurist - they are, who's kidding who, the equivalent of cli-fi authors in the world of science and business - this futurist, who runs scenarios workshops with the likes of NASA scientists, said that humans have the power to create the future ... but telling stories of the future we want to see.

It'd be an interesting conversation to look at the works of cli-fi authors. How many of their stories are doom and gloom, about a dark and hopeless future that's been brought about by the climate crisis? And how many work, in their novels, through the doom and gloom horrors to show us how we might get to a better future?

I need to pick up with Parable of the Sower again but I think the genre is needed. What damage we have to the environment has made (some) irreparable changes. If we are compelled to action, inspired, and moved by fiction, then this is the time for our entertainment to inform us. Dystopias are visions of what feels like the worst case scenario, but cli fi feels like that bridge better here and that future. No stacked skyscrapers and a scorched sky, but suspicious and dangerous neighbors, true resource scarcity, and the parched mouths of dying citizens. Perhaps cli fi will show us the 10 feet in front of us so we can make radical direction changes.