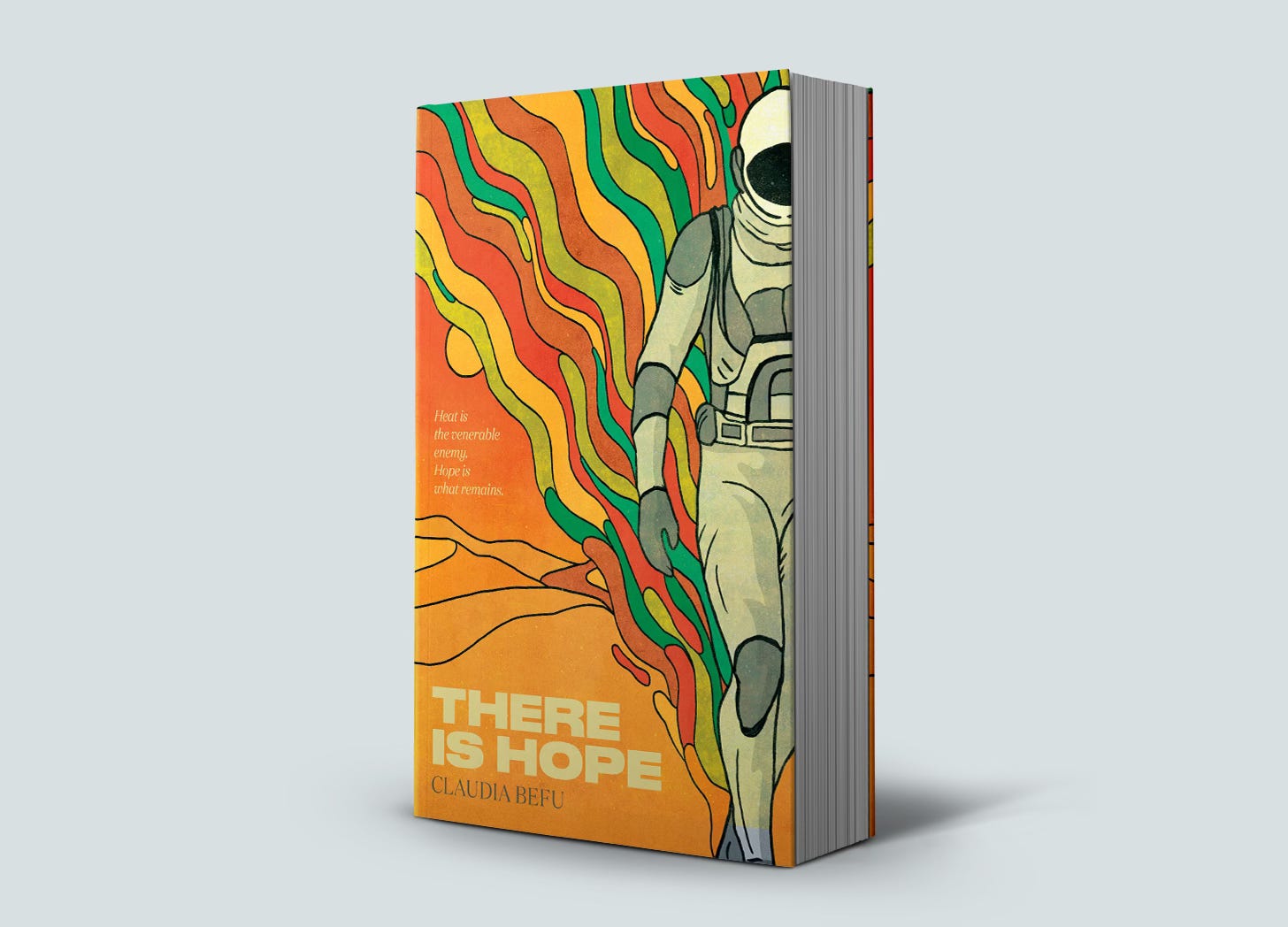

I'm writing a climate fiction series

The genesis of "There Is Hope" on Substack

In 2006 I read Oryx and Crake, a novel by one of my all-time favorite writers Margaret Atwood. If I were to write a screenplay based on the book, this would be the logline:

In a post-apocalyptic world, humanity was wiped out by a synthetic virus and replaced with a bio-engineered species of herbivorous humanoids called Crakers.

I remember only a few novels as often and …